Introduction

Fusarium species are important pathogens in agriculture and animal production, capable of causing several diseases in plants and animals. Among the most notable is fusariosis, which primarily affects cereal crops. These diseases not only reduce crop quality and yield but also have serious implications for animal and human health due to mycotoxin production. More than 200 Fusarium species have been classified, each with distinct pathogenic potential and mycotoxin production profiles. The most common species include Fusarium graminearum, Fusarium verticillioides and Fusarium culmorum (Ekwomadu et al., 2023).

Fusarium head blight

Fusarium Head Blight (FHB) is a disease caused by several Fusarium species, particularly Fusarium graminearum. It affects cereal crops during the flowering stage, especially wheat (Triticum spp.) and barley (Hordeum spp.). The characteristic signs include a premature discoloration of the infected spikelets, which may progress to affect the entire head, leading to significant economic losses (Image 1) (Karlsson et al., 2021).

Image 1. Wheat infected with Fusarium Head Blight.

The spread of Fusarium fungi occurs mainly through spores dispersed by air or water, which infect the heads of cereal plants. The spread process involves spore germination followed by penetration into plant tissues.

Their expansion in crops is favoured by high humidity, especially during crop flowering and grain filling. Warm temperatures between 22 and 28 °C also promote Fusarium infection and disease development (Bernnan et al., 2005).

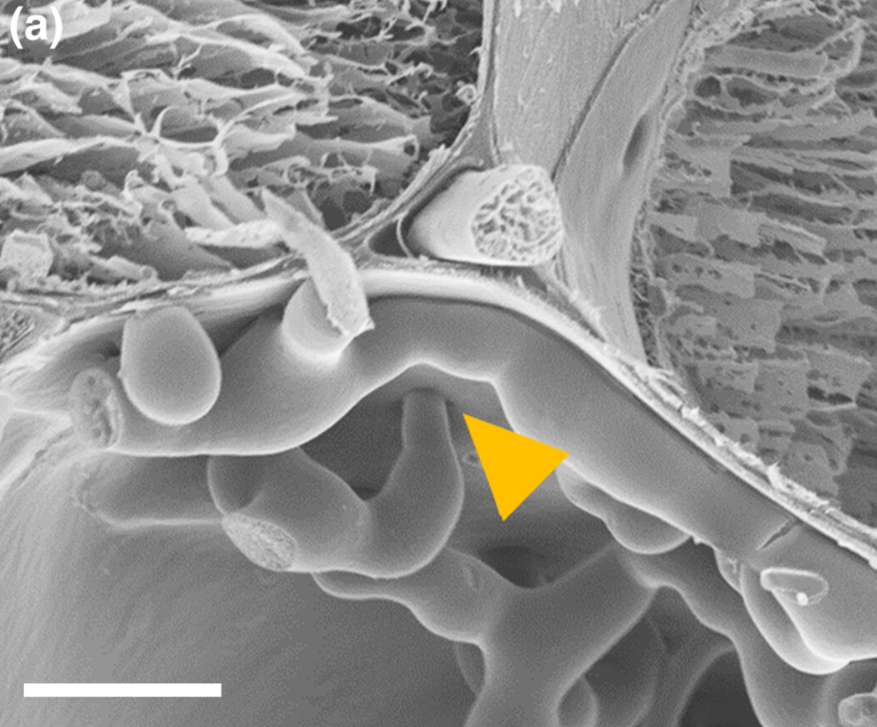

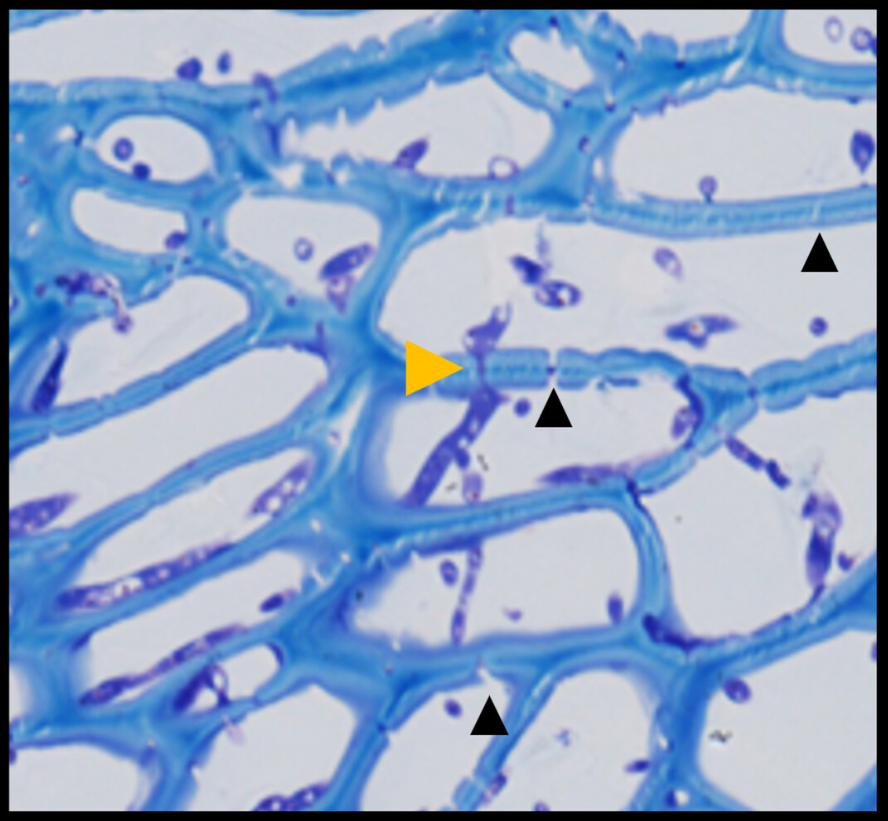

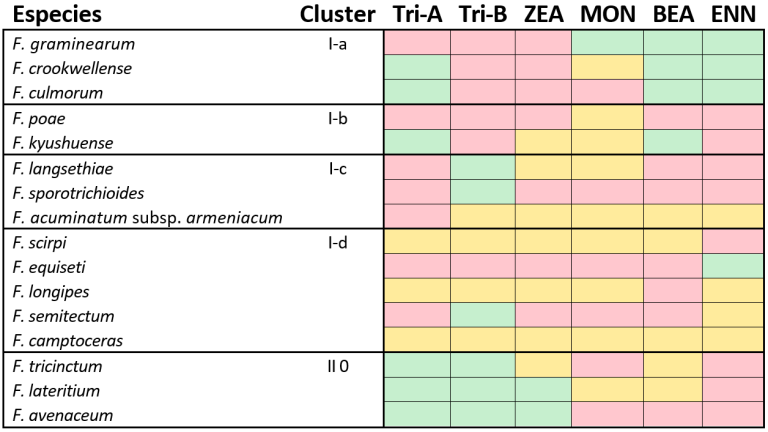

This expansion of the fungus occurs through the plasmodesmata, the channels in the cell walls that connect plant cells (Image 2).

Image 2. A) Electron microscopy image showing the expansion of Fusarium through the plasmodesmata connecting plant cells.

B) Microscopy image showing the expansion of Fusarium through the plasmodesmata connecting plant cells (Armer et al., 2024).

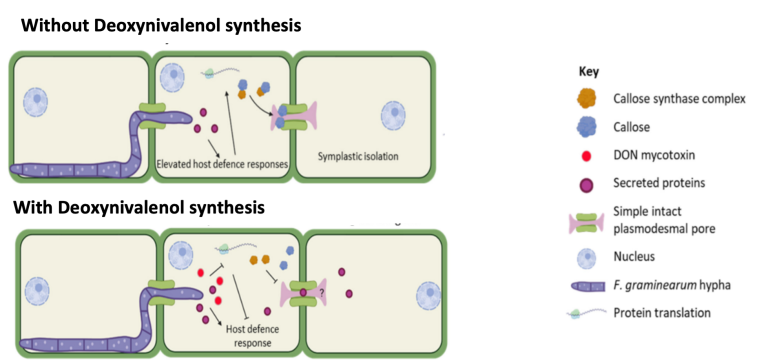

During the expansion of Fusarium within plant tissues, the host activates a series of defence mechanisms to hinder or prevent further expansion. Key defence responses include increased protein secretion and callose deposition to block the plasmodesmata, thereby preventing spread to adjacent cells.

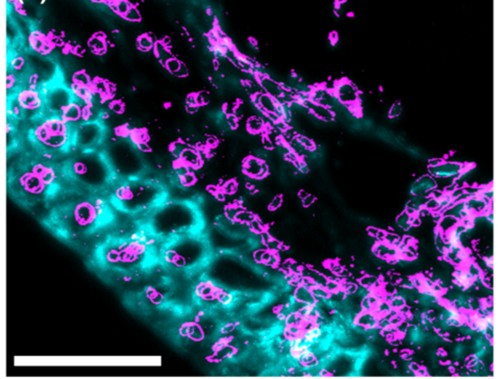

To counteract the innate defence mechanisms of the host, Fusarium species synthesise secondary metabolites known as mycotoxins. Among these, deoxynivalenol (DON) is particularly important, as it can suppress plant defences by reducing cellular protein synthesis and decreasing callose deposition. As a result, weakened plant defences allow Fusarium to spread more rapidly within plant tissues (Armer et al., 2024).

Image 3. Diagram showing Fusarium expansion without DON synthesis and with DON synthesis (Armer et al., 2024).

Image 4. Immunofluorescence images showing callose deposition (pink) in response to Fusarium attack:

A) Callose deposition 5 days after Fusarium infection without trichothecene synthesis.

B) Callose deposition 5 days after Fusarium infection with trichothecene synthesis (Armer et al., 2024).

Mycotoxins produced by fungi of the genus fusarium

In addition to trichothecenes, fungi of the genus Fusarium produce a range of other mycotoxins, each with distinct characteristics and effects on plants. Among those most notable for their prevalence and toxicity are:

Trichothecenes

- Deoxynivalenol (DON)

- Inhibition of growth: inhibits protein synthesis, reducing the growth of roots and shoots.

- Cell damage: causes the loss of chlorophyll and other photosynthetic pigments, leading to leaf bleaching and, eventually, necrosis.

- Loss of membrane integrity: increases plasma membrane permeability, causing electrolyte leakage and cell death.

- Induction of apoptosis: can trigger programmed cell death in plant cells via the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS).

- T-2 and HT-2 mycotoxins

- Inhibition of protein synthesis: these toxins disrupt ribosomal function, blocking protein synthesis and consequently inhibiting plant growth.

- Morphological distortion: in certain plant species, T-2 can alter morphology, causing dwarfism, twisted leaves, and other deformities.

- Induction of oxidative stress: these toxins elevate ROS levels, leading to oxidative damage and cell death.

Fumonisins:

- Interference in sphingolipid biosynthesis: fumonisins inhibit ceramide synthase, a key enzyme in sphingolipid synthesis, thereby disrupting cell membranes and cellular signalling.

- Necrosis and chlorosis: the accumulation of toxic sphingolipid intermediates leads to tissue necrosis and leaf chlorosis, particularly in maize (Zea mays).

- Growth reduction: fumonisins have been shown to inhibit root elongation and impair seedling development.

Zearalenone (ZEN)

- Alteration of membrane permeability: ZEN can disrupt plasma membrane permeability, leading to electrolyte leakage.

- Inhibition of root growth: ZEN reduces ATPase activity, negatively affecting root development in crops such as maize.

- Cellular acidification: interferes with proton extrusion, resulting in cellular acidification and affecting overall plant metabolism.

Fusarin C:

- Mutagenicity: certain fusarins, such as fusarin C, are mutagenic compounds that can disrupt cell division in plants.

- Membrane damage: can compromise the integrity of cell membranes, leading to cell lysis and tissue death.

Moniliformin (MON):

- Inhibition of leaf development: reduces the efficiency of photosynthetic pigments, affecting leaf development.

- Biomass reduction: can reduce seedling biomass and impair overall plant growth.

Enniatins (ENNs) and beauvericin (BEA):

- Mitochondrial damage: ENNs and BEA can trigger apoptosis in plant cells by disrupting mitochondrial function.

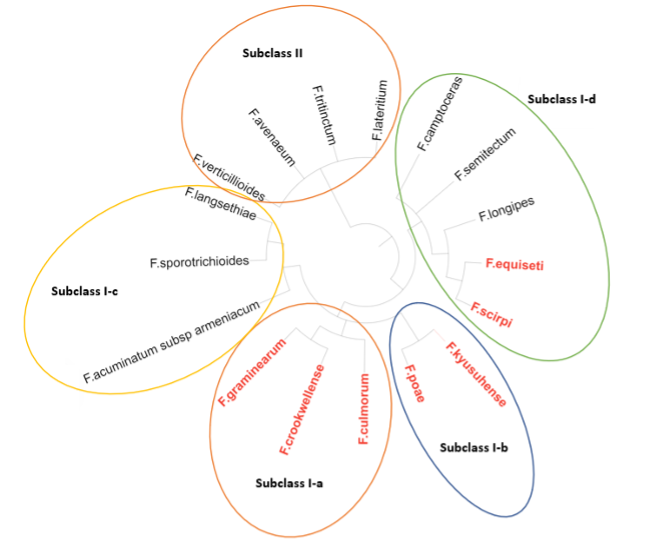

Each of these mycotoxins has a distinct toxicity profile. However, not all Fusarium species are capable of producing every mycotoxin, due to impaired biosynthetic pathways resulting from enzymatic deficiencies or mutations (Table 1).

Table 1. Classification of Fusarium species with the potential to produce mycotoxins.

Red = Potential to produce the mycotoxin.

Green = No potential to produce the mycotoxin.

Orange = Insufficient data to determine whether the species has the potential to produce the mycotoxin.

Phylogenetic analysis groups Fusarium species into five clusters (Subclass I-a, Subclass I-b, Subclass I-c, Subclass I-d, and Subclass II). Image 5 shows the correlation between these clusters and their mycotoxin production profiles. For example, species within Subclass II, Subclass I-c, and certain species of Subclass I-d are incapable of synthesising DON (Watanabe et al., 2011).

Image 5. Phylogenetic classification of Fusarium species.

Metabolic pathways and trichothecene synthesis

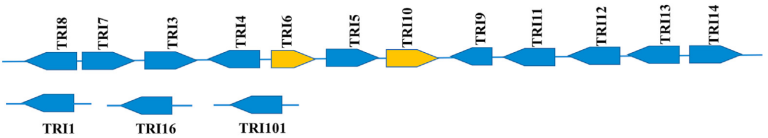

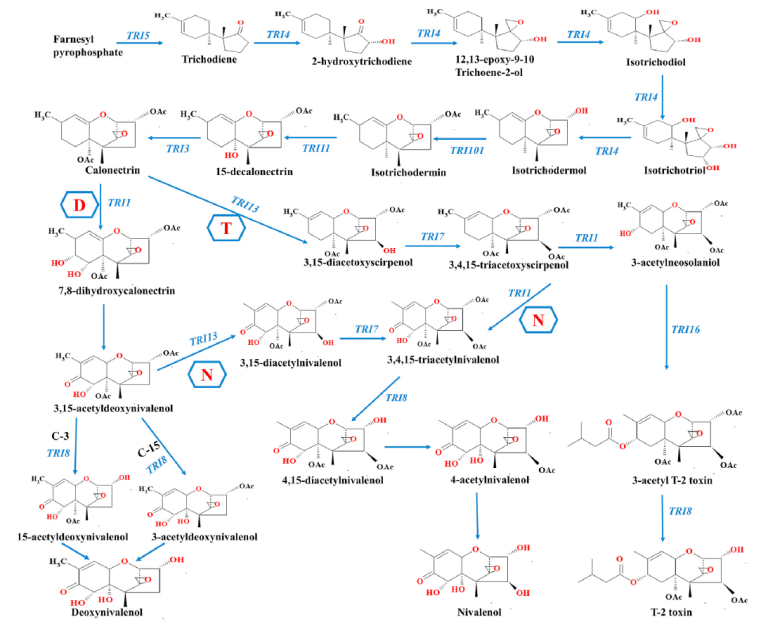

Trichothecenes, including Type A (T-2 and HT-2 toxins) and Type B (DON and nivalenol), are synthesised via a single, shared biosynthetic pathway in Fusarium species. This pathway is regulated by a group of genes known as the TRI cluster (Image 6). Key genes within this cluster include TRI6 and TRI10, which act as regulators, and TRI13 and TRI7, which determine the trichothecene profile produced by a given Fusarium strain (Image 7). Variability in trichothecene synthesis may be influenced by environmental factors, such as temperature and humidity, as well as by the specific Fusarium species.

Image 6. TRI cluster: group of trichothecene biosynthetic genes (TRI) in Fusarium graminearum (Meneely et al., 2023).

Image 7. Proposed trichothecene biosynthesis pathways. N: pathway in nivalenol-producing strains; D: pathway in deoxynivalenol-producing strains; T: pathway in T-2 toxin-producing strains (Meneely et al., 2023) MetaCyc pathway database

The type of trichothecenes produced vary considerably depending on the Fusarium species and on external factors such as geographic region, climate, and agricultural practices. Studies have shown that Fusarium strains can modulate their trichothecene production in response to specific environmental conditions. This highlights the importance of understanding the regulation of these genes to manage the risks associated with mycotoxin contamination (Kolawole et al., 2021; Brown et al., 2015).

Conclusions

The production of mycotoxins by fungi of the genus Fusarium depends on both the fungal species and environmental conditions. Some Fusarium species may not synthesise certain mycotoxins, while others can produce them abundantly under specific circumstances. Understanding these factors is essential for developing effective prevention and control strategies in agriculture and animal nutrition.