Introduction

Fungi of the genus Aspergillus are ubiquitous microorganisms found in air, soil, and decomposing organic matter, and comprise more than 250 species. Although some species have industrial applications, such as in the production of fermented foods or enzymes, others pose a significant threat to human, animal, and plant health due to their ability to produce mycotoxins (Klich, 2007).

These fungi are the principal producers of aflatoxins, highly toxic mycotoxins that form under specific environmental conditions and are associated with numerous issues across the global food chain. As climate change intensifies the conditions that favour the proliferation of Aspergillus species, the regulation and control of these toxins is becoming increasingly critical.

Morphological characteristics

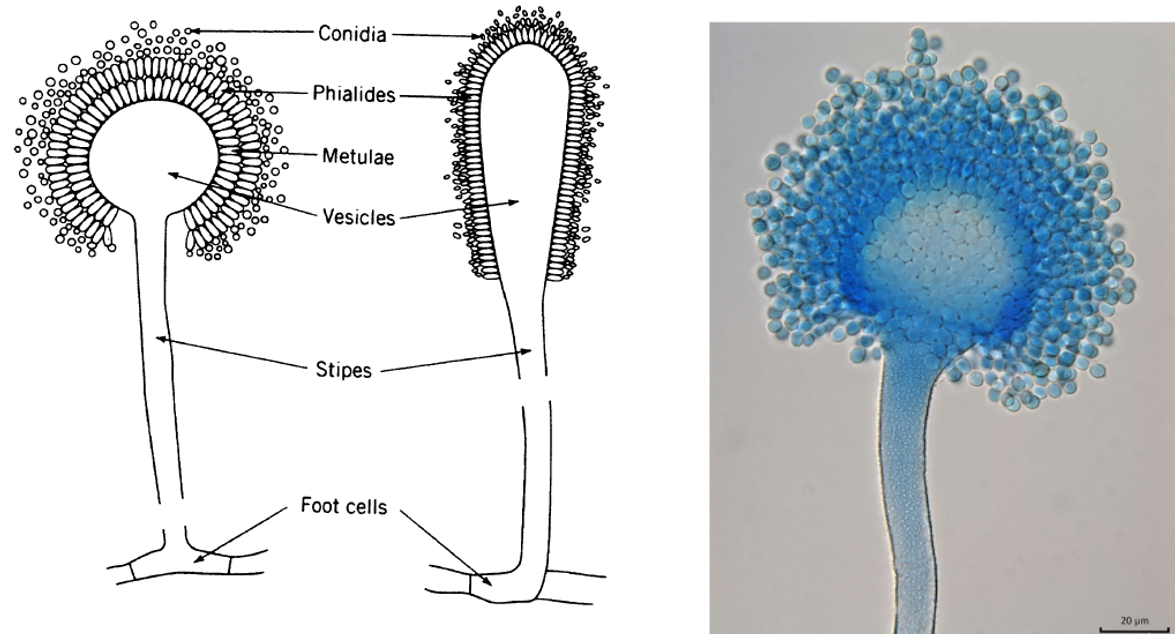

Aspergillus species are filamentous fungi characterised by their ability to reproduce asexually through the formation of conidia. Their morphology is defined by a characteristic architecture that enables the efficient dispersal of spores. The different components are shown in Image 1.

Image 1. A) Microscope image of Aspergillus (Pickova et al., 2021).

B) Aspergillus morphology (Klich, 2009).

Conidiophores:

Conidiophores are elongated, erect structures that arise from foot cells (basal cells). They serve as supporting elements of the conidial apparatus and bear a rigid stipe that may be smooth or rough, depending on the species. Their length and diameter can vary among species, but they always terminate in a characteristic vesicle.

Vesicles:

The vesicle is a globose or clavate structure situated at the apex of the conidiophore. Phialides—and in some species, metulae—arise from it. Its size and shape represent important taxonomic features for fungal identification.

Metulae and Phialides:

- Metulae: Elongated, conical cells arranged radially around the vesicle in species with a biseriate organisation. They serve as a base for the phialides.

- Phialides: Specialized structures that arise directly from the vesicle (in uniseriate species) or from the metulae (in biseriate species). Phialides are responsible for the production of conidia via a repeated budding mechanism.

Conidia:

Conidia are spherical or subspherical asexual structures arranged in basipetal chains, with the youngest spores forming at the base of the chain. They may be smooth or rough, depending on the species, and contain melanin, which provides resistance to adverse environmental conditions. Conidia serve as the dispersal units of the fungus.

Basal or foot cells:

Basal, or foot, cells form the base of the conidiophore and anchor it to the substrate. Their shape and size contribute to the support of the conidial apparatus (Klich, 2007).

Mycotoxins produced by Aspergillus

Within the genus Aspergillus, certain species are notable for their high mycotoxin production, particularly Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus. These toxins have no clearly defined role in fungal growth or development and are therefore classified as secondary metabolites. Their synthesis is thought to occur under specific conditions, serving defensive or protective functions in response to environmental stress (Suárez et al., 2013). It has also been suggested that these toxins facilitate the colonisation of weakened or damaged plant tissues, thereby enhancing fungal survival (Varga et al., 2003).

Among the most dangerous mycotoxins produced by the genus Aspergillus are aflatoxins, which are considered potent carcinogens that can contaminate crops such as maize, wheat, and rice.

These mycotoxins are the most strictly regulated, having been historically linked to major contamination events that resulted in numerous deaths. One of the earliest cases occurred in 1961 on a poultry farm in London, where 100,000 turkeys died from the so-called “turkey X disease” after being fed Brazilian peanut meal contaminated with aflatoxins (Blount et al., 1961).

In addition to aflatoxins, the genus Aspergillus is known to produce other mycotoxins, as shown in the following table (Ráduly et al., 2020).

| Aspergillus species | Aflatoxins | Ochratoxin | Citrinin | Patulin | Cyclopiazonic Acid | Aflatrem | Terrain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. alliaceus | X | ||||||

| A. arachidicola | X | ||||||

| A. arachidicola sp. nov. | X | ||||||

| A. bombycis | X | ||||||

| A. carbonarius | X | ||||||

| A. flavus | X | X | X | ||||

| A. korhogoensis | X | ||||||

| A. minisclerotigenes sp. nov. | X | X | |||||

| A. niger | X | ||||||

| A. nomius | X | ||||||

| A. novoparasiticus | X | ||||||

| A. ochraceus | X | ||||||

| A. parasiticus | X | ||||||

| A. pseudotamarii | X | ||||||

| A. rambellii | X | ||||||

| A. terreus | X | X | X | X | |||

| A. toxicarius | X |

Table 1. Mycotoxins produced by Aspergillus species.

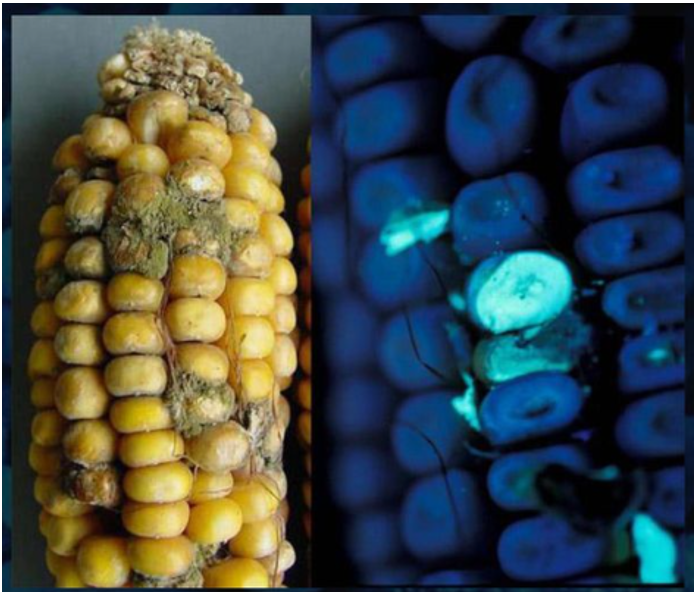

It should be noted that among the aflatoxins, the most significant are B1, B2, G1, and G2 in crops, and M1 in milk. The B and G nomenclature refers to the fluorescence emitted by the molecules (B = blue, G = green) (Image 2). Aflatoxin M1 is a metabolite formed through the biotransformation of aflatoxin B1 and is notable for its accumulation in milk.

Image 2. Fluorescence emitted by aflatoxins in maize contaminated with Aspergillus.

Effects of mycotoxins on crops and public health

From an agricultural perspective, Aspergillus infections can result in substantial economic losses. For instance, infections by Aspergillus flavus can reduce total crop yields by 10-30% (Ramírez-Camejo et al., 2012). Contamination primarily occurs under warm, humid conditions, compromising both the quality and quantity of the crops. Furthermore, contaminated foods often have to be destroyed, further increasing costs for producers.

Aspergillus mycotoxins not only compromise food quality but also pose significant risks to animal and human health. In livestock, ingestion of mycotoxin-contaminated feed can lead to liver disease, immunosuppression, and reproductive disorders, thereby affecting productivity. In humans, exposure to aflatoxins has been associated with serious conditions such as liver cancer, and their presence in food can result in acute food poisoning.

The impact of climate change on mycotoxin production

Climate change is altering temperature and rainfall patterns worldwide, creating conditions that increasingly favour the proliferation of mycotoxin-producing fungi such as Aspergillus species. Droughts, heatwaves, and shifts in growing seasons directly influence crop vulnerability, potentially promoting fungal infection and, consequently, the production of mycotoxins.

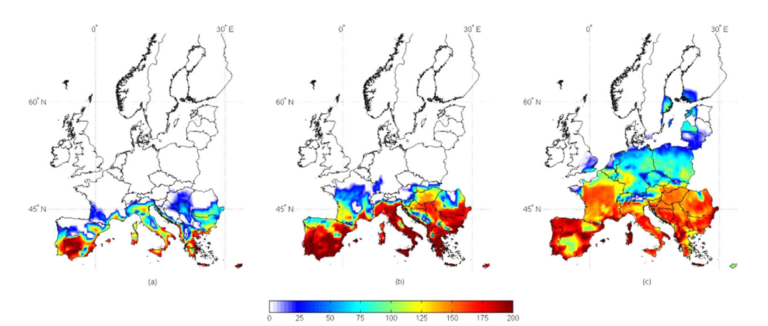

Higher temperatures and increased humidity provide an optimal environment for the growth of Aspergillus and the synthesis of mycotoxins. Recent studies have reported rising aflatoxin levels in regions where they were previously not a concern, possibly due to the expansion of climatic zones suitable for fungal growth. For instance, some European countries, traditionally free of aflatoxins, are now beginning to face problems with these toxins as a result of rising temperatures (Image 3) (Battilani et al., 2016).

Image 3. (Battilani et al., 2016).

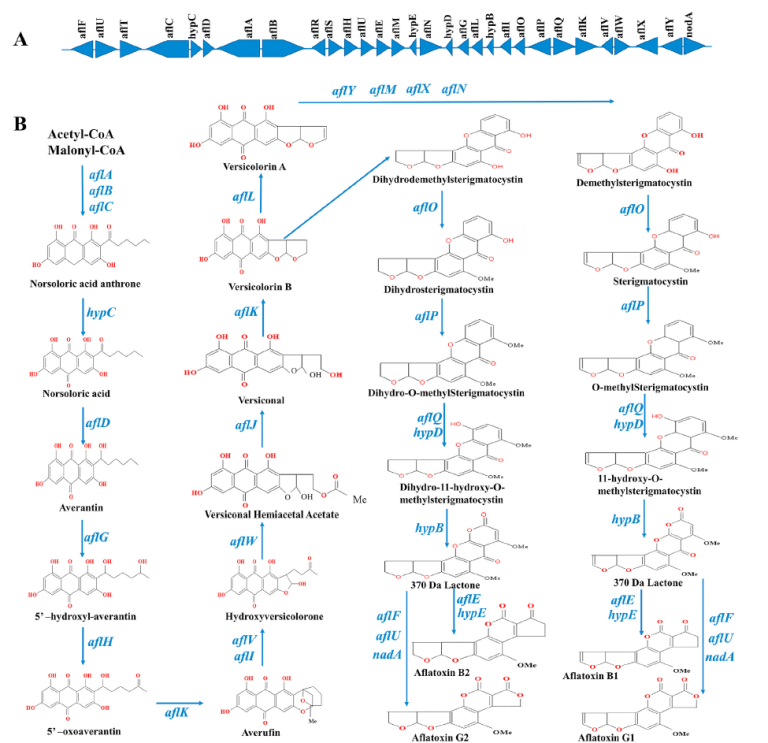

Metabolic pathways and aflatoxin synthesis

Aflatoxins are bisfuranocoumarin compounds produced by more than 16 Aspergillus species. Aflatoxins of the B series (AFB1 and AFB2) and the G series (AFG1 and AFG2) are the most widely recognized due to their toxicity and prevalence. Their biosynthesis is a highly regulated process that involves three groups of genes, depending on the stage of the metabolic pathway:

- Early-pathway genes: aflA, aflB, aflC, hypC, and aflD, which initiate the conversion of hexanoate to norsolorinic acid.

- Intermediate-pathway genes: aflG, aflH, aflK, aflV, and aflW, responsible for converting intermediates such as averufin into precursors such as versiconal hemiacetal acetate (VHA).

- Late-pathway genes: aflP, aflQ, hypB, and others, which catalyse the final transformations leading to AFB1, AFB2, AFG1, and AFG2. The regulatory gene aflR controls the expression of many pathway genes, while aflS acts as a co-activator in the early stages of biosynthesis.

Regarding specific differences and environmental factors:

- Aspergillus flavus mainly produces B-type aflatoxins (AFB1 and AFB2), whereas Aspergillus parasiticus produces both B-type and G-type aflatoxins.

- The inability of Aspergillus flavus to synthesize G-type aflatoxins is due to a deletion in the aflF and aflU genes. However, new A. flavus strains capable of producing all four aflatoxins have been identified.

- Aflatoxin production is influenced by environmental factors and may vary according to species and environmental conditions. This knowledge of biosynthetic pathways and genetic regulation enables the development of strategies to mitigate aflatoxin production and enhances our understanding of metabolic diversity among mycotoxigenic species.

This summary outlines the key aspects of aflatoxin biosynthesis and regulation in Aspergillus species (Kolawole et al., 2021).

Image 4. A) Aflatoxin biosynthetic gene cluster in Aspergillus species. Arrows indicate the direction of genetic transcription, and regulatory genes are marked in blue.

B) Proposed aflatoxin biosynthetic pathway.

(Ehrlich et al., 2004; Skory et al., 1992; Yu et al., 2004).

Regulation and strategies to mitigate risk

Mycotoxin regulation is essential to ensuring food safety and protecting public health. In many countries, strict limits are in place for the permissible concentrations of mycotoxins in food and feed. For example, the European Union has established maximum levels of aflatoxins permitted in agricultural products intended for both human consumption and animal nutrition.

Given its toxic potential, the legal limits for AFB1, one of the best-known aflatoxins, are currently regulated by Commission Regulation (EU) No. 574/2011, which amends Annex I of Directive 2002/32/EC.

| Raw materials/Feed | Legal limit (ppb), based on feed with 12% moisture |

|---|---|

| All raw materials for animal nutrition | 20 |

| Compound feed for cattle, sheep, and goats (excluding dairy animals, calves, and lambs) | 20 |

| Complete feed for dairy cattle | 5 |

| Complete feed for calves and lambs | 10 |

| Compound feed for pigs and poultry (excluding young animals) | 20 |

| Other complete feed | 10 |

| Other complementary feed | 5 |

Table 2. Established legal limits for AFB1 in animal feed.

However, as climate change drives an increase in mycotoxin prevalence, current regulations may become outdated. A global approach is required, incorporating active monitoring of environmental conditions and the presence of mycotoxins in crops.

Conclusion

Fungi of the genus Aspergillus and their capacity to produce mycotoxins pose a growing threat in the context of climate change. Global warming is creating increasingly favourable conditions for the proliferation of these fungi, jeopardising food safety as well as human and animal health.

To mitigate this risk, it is essential to strengthen regulation, promote research, and implement adaptation strategies to protect crops from Aspergillus infections and reduce exposure to mycotoxins. Preventive measures include good agricultural practices, proper storage management, grain ventilation, and pest control. These actions can substantially decrease the incidence of mycotoxins in animal feed.