Beyond apoptosis: The uniqueness of ferroptosis

While the focus has traditionally been placed on apoptosis or necrosis, modern science has identified a new key player in cellular degradation: ferroptosis. This process is defined as a non-apoptotic form of programmed cell death, which is distinguished from apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy by both its molecular mechanisms and morphological characteristics (Dixon et al., 2012; Ali et al., 2025; Chen et al., 2025).

Formally identified in 2012, ferroptosis is essentially described as a lethal process driven by lipid peroxidation. Unlike other pathways, its diagnostic features are primarily observed in the mitochondria, which exhibit characteristic shrinkage, the reduction or disappearance of their cristae, outer membrane rupture, and increased bilayer density (Chen et al., 2025; Ding et al., 2023; Fan et al., 2025; He et al., 2024; Huangfu et al., 2025; Søderstrøm et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2025; Yu et al., 2025).

The failure of homeostasis and lipid peroxidation

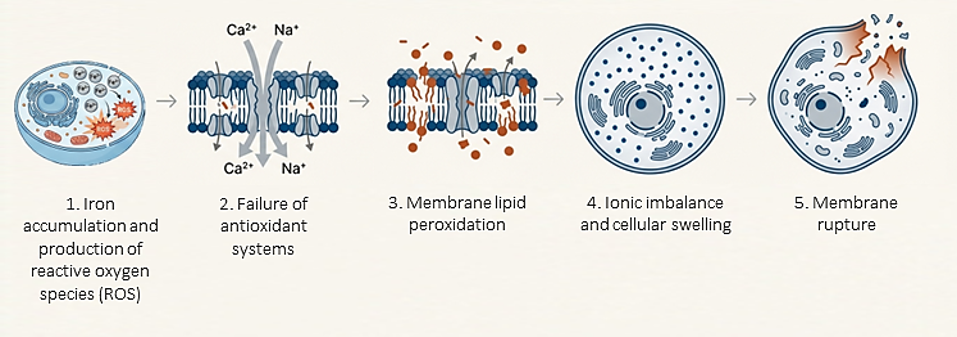

Ferroptosis begins with a disruption in iron homeostasis, leading to an increase in free ferrous iron (Fe2+) within the cytoplasm (Dixon et al., 2024; Zhu et al., 2025). This excess of free iron triggers the so-called Fenton reaction, which generates a massive accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that attack cellular structures (Guan et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2024; Zhu et al., 2025).

For ferroptosis to progress, the cell must lose its ability to neutralize this oxidative stress. The most critical defense mechanism is the system Xc-/GSH/GPX4 axis (Ali et al., 2025; Chen et al., 2025). Inhibition of the Xc- transporter prevents cystine uptake, which depletes levels of glutathione (GSH), the primary cellular antioxidant (Huangfu et al., 2025; Tian et al., 2025; Zhu et al., 2025). Without GSH, the enzyme glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) becomes inactivated or degraded (Ali et al., 2025; Ding et al., 2023; Zhu et al., 2025).

In the absence of a functional antioxidant defense, free radicals and iron attack the polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) present in cellular and organelle membranes (Ali et al., 2025; Ding et al., 2023; Dixon et al., 2024). This uncontrolled oxidation damages membrane integrity, increasing both tension and permeability (Ali et al., 2025; Dixon et al., 2024; Fan et al., 2025). This leads to the activation of ion channels, allowing a massive influx of calcium (Ca2+) and sodium (Na+), along with an efflux of potassium (K+) (Dixon et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2022). The loss of ionic homeostasis triggers an osmotic water influx, resulting in cellular and organelle swelling (Dixon et al., 2024; He et al., 2024; Søderstrøm et al., 2022).

Ultimately, all of this leads to the physical collapse of the cell. The plasma membrane ruptures, releasing intracellular contents (Figure 1) (Dixon et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2022; Mou et al., 2019).

Figure 1. The process of ferroptosis.

Mycotoxins: Activators of ferroptosis

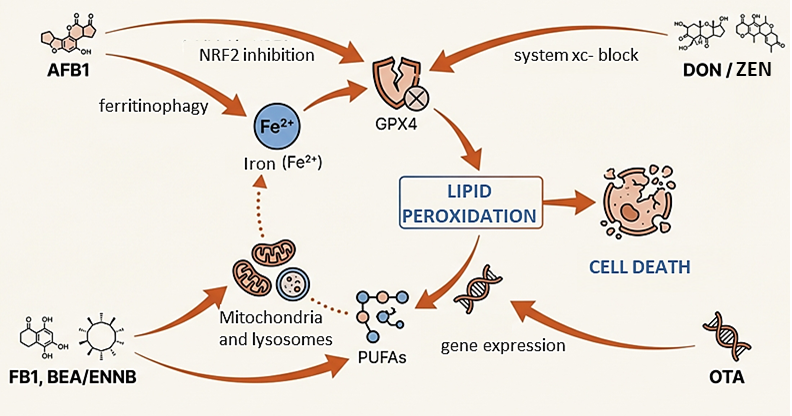

The activation of ferroptosis by mycotoxins follows a coordinated offensive through three interconnected pathways: the disruption of iron metabolism, the depletion of the GPX4 antioxidant system, and the massive accumulation of lipid peroxides (Zhu et al., 2025). Toxins such as aflatoxin B1 (AFB1), deoxynivalenol (DON), and zearalenone (ZEN) act as catalysts for this process, generating levels of ROS that overwhelm the cell’s natural defenses (Ding et al., 2023; Zhu et al., 2025).

Specific mechanisms of action

AFB1 exerts its toxicity in two ways: on one hand, it inhibits the NRF2 signaling pathway, causing a drastic drop in GSH and the inactivation of the GPX4 enzyme (Chen et al., 2025; Zhu et al., 2025). On the other hand, it promotes ferritinophagy, a ferritin degradation process, which releases large amounts of ferrous iron (Fe2+) into the cytoplasm, directly fueling the Fenton reaction (Song et al., 2024; Zhu et al., 2025).

Along similar lines, DON compromises the viability of key organs such as the liver, intestine, and reproductive organs by inhibiting the SLC7A11-GSH-GPX4 axis (Guan et al., 2025; Zhu et al., 2025). Recent research suggests that its impact is even more profound, altering glycolysis and silencing, through epigenetic mechanisms, genes crucial for iron homeostasis (Fan et al., 2025).

For its part, ZEN activates the p53 tumor suppressor pathway to block cystine entry into the cell, which prevents GSH synthesis and leaves the cell membrane fully exposed to peroxidation (Wang et al., 2025; Xiong et al., 2025; Zhu et al., 2025).

Ochratoxin A (OTA) utilizes epigenetic remodeling to silence antioxidant genes while activating those that promote ferroptosis (Ali et al., 2025).

Meanwhile, T-2 toxin specifically targets the ferritin reserve and GPX4, causing severe damage to cardiac and testicular tissues (He et al., 2024; Zhu et al., 2025).

Finally, fumonisin B1 (FB1) triggers this process through mitophagy, generating a mitochondrial iron imbalance that culminates in a lethal increase of ROS (Figure 2) (Zhu et al., 2025).

Figure 2. Mechanisms of action of major mycotoxins.

From cellular damage to productive and systemic impact

The activation of ferroptosis by mycotoxins should not be understood as an isolated cellular event, but rather as the trigger for systemic deterioration that compromises profitability and animal welfare. This process manifests critically across the primary pillars of production.

Reproductive challenges and damage to hereditary material

In swine production, ZEN induces ferroptosis in endometrial stromal cells (ESCs) and the ovaries, compromising pregnancy and uterine health (Wang et al., 2025; Zhu et al., 2025). In piglets, DON promotes ovarian damage by inhibiting glycolysis and the synthesis of essential steroid hormones, such as progesterone and estradiol (Fan et al., 2025).

In poultry, AFB1 severely affects the growth and development of primordial germ cells (PGCs), reducing reproductive potential from embryonic stages (Niu et al., 2025). In males, toxins such as T-2 and ZEN cause the degradation of spermatogenesis and testicular atrophy (He et al., 2024; Zhu et al., 2025).

Intestinal barrier compromise

The gastrointestinal tract, the body’s first line of defense, suffers profound structural damage. Mycotoxins such as DON and citrinin (CTN) cause villi shedding, glandular damage, and the disruption of tight junctions, which increases intestinal permeability (Huangfu et al., 2025; Lim et al., 2025; Zhu et al., 2025). This leads to reduced feed efficiency, chronic diarrhea, and increased susceptibility to enteric pathogens (Huangfu et al., 2025; Zhu et al., 2025). Furthermore, the co-exposure of DON with metals such as copper synergistically enhances this intestinal toxicity (Zhong et al., 2025).

Severe nephrotoxicity and hepatotoxicity

OTA is a potent nephrotoxin that causes glomerular atrophy and inflammatory infiltration in broilers (Tian et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2024). In parallel, AFB1 and DON trigger hepatotoxicity characterized by liver hemorrhages, necrosis, and a drastic drop in the liver’s detoxification capacity, directly affecting weight gain (Guan et al., 2025; Liu et al., 2025; Zhu et al., 2025).

Immunosuppression and lymphoid atrophy

AFB1-induced ferroptosis affects key lymphoid organs, such as the bursa of Fabricius in chickens, causing atrophy and reducing lymphocyte populations (Xia et al., 2024). This leaves animals vulnerable to environmental health challenges and reduces the efficacy of vaccination programs (Xia et al., 2024; Zhu et al., 2025).

Impact in aquaculture

In species such as the grass carp, AFB1 significantly reduces feed intake and the specific growth rate by inducing ferritinophagy and structural damage to the liver (He et al., 2025). On the other hand, emerging mycotoxins such as beauvericin (BEA) and enniatins (ENNs) also compromise hepatocyte viability in Atlantic salmon by altering iron homeostasis (Søderstrøm et al., 2022).

Conclusion

Understanding ferroptosis as a central mechanism of mycotoxicosis opens a new frontier for the animal nutrition industry. By identifying this pathway, it is now possible to develop much more precise mitigation strategies.

The use of natural antioxidants, such as curcumin, have demonstrated an exceptional ability to reactivate the GPX4 axis, protecting cellular integrity against mycotoxin attacks (Chen et al., 2025; Tian et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2025; Zhu et al., 2025). Ultimately, controlling ferroptosis not only improves productive performance but also ensures food safety and the sustainability of animal production chains (Zhu et al., 2025).