Introduction

Ruminants are considered less susceptible to the effects of mycotoxins compared to other species. Biotransformation processes that occur in the rumen microbiota convert some of these substances into less toxic compounds for these animals (Xu et al., 2023). However, mycotoxins have been shown to remain detrimental to livestock production, and alteration of the ruminal environment can hinder detoxification (Álvarez-Días et al., 2022).

Some mycotoxicosis cause acute or chronic diseases with evident clinical signs and pathologies. But it should be noted that they can cause subclinical diseases or productivity declines, as well as carcinogenic, mutagenic, teratogenic, immunosuppressive, and endocrine effects, which are difficult to diagnose.

These diseases can negatively influence the performance and productivity of ruminants, leading to reproductive problems and triggering states of immunosuppression (Álvarez-Días et al., 2022). A clear correlation has been established between the presence of mycotoxins in dairy cattle feed and feed refusal, a drop in milk production, diarrhea, and infertility (Ismail et al., 2020). The offspring of exposed animals are also affected. In cattle exposed to aflatoxins, offspring more susceptible to inflammatory processes and secondary infections have been detected. Furthermore, mycotoxins cause hepatic and renal damage (Álvarez-Días et al., 2022).

Aflatoxins

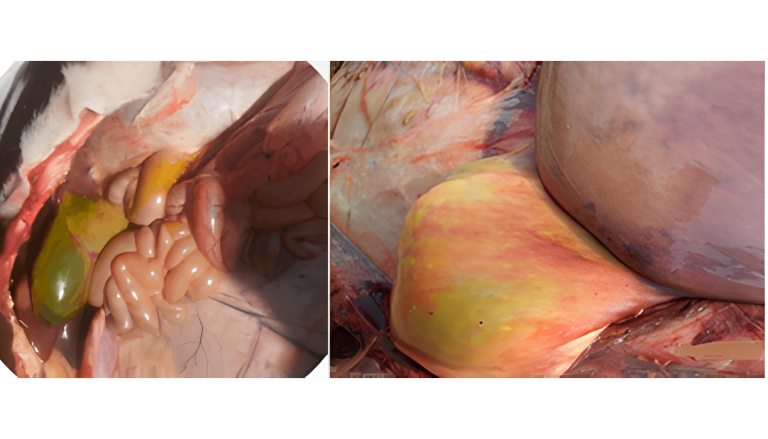

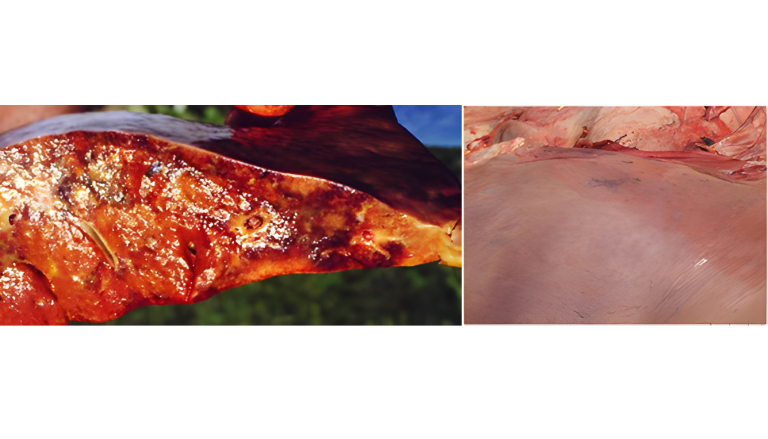

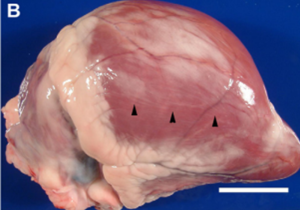

Aflatoxins represent a high risk in ruminants, especially in dairy cows, due to their demonstrated transfer to milk intended for human consumption or calf feeding (Hernández-Valdivia et al., 2021). Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) is the best known in this family and its pathological effects are severe, notable on necropsy: hepatic fibrosis with bile duct cell proliferation, megalocytosis, and bile stasis (Image 1). Additionally, exposure to this mycotoxin can result in hepatomegaly (Image 2) or a hemorrhagic liver with a pale bronze texture, as well as congestive liver and heart and hemorrhagic kidneys (Image 3 and Image 4) (Sajid Umar et al., 2015; Ismail et al., 2020; Álvarez-Días et al., 2022). In subacute or chronic presentations, subcutaneous and subserosal hematomas and hemorrhagic enteritis with evident jaundice may be observed.

Image 1. Enlargement, biliary stasis, and hemorrhage.

Image 2. Morphological changes (hepatomegaly) and necrosis.

Image 3. Soft perirenal fat and hemorrhages.

Image 4. Renal and cardiac congestion.

Beyond organ lesions, AFB1 causes immunosuppression, which increases susceptibility to secondary infections and affects productivity (Riet-Correa et al., 2013). Clinical signs described in animals include: inappetence, depression, diarrhea, and epistaxis (Image 5) (Sajid Umar et al., 2015; Ismail et al., 2020; Álvarez-Días et al., 2022). In calves, a nervous condition with blindness and convulsions is observed (Perusia & Rodriguez, 2017).

Image 5. Diarrhea, loss of appetite, loss of body condition, and epistaxis.

Other documented effects include abortion (Image 6) and increased mortality and prolapses (Image 7) (McKenzie et al., 1981; Van Halderen et al., 1988; Felipe Penagos-Tabares et al., 2024).

Image 6. Abortions at 100 days (A), 215 days (B), and 260 days (C) of gestation.

Image 7. Prolapses (uterine and vaginal).

Zearalenone

As in other species, zearalenone (ZEA) in ruminants fundamentally induces reproductive alterations. Its estrogenic effect can lead to fertility problems, vulvar inflammation (vulvovaginitis) alterations in the reproductive cycle, and notably, enlargement of the uterus and udder thickening. Rectal prolapse, vulvar enlargement, and uterine prolapse (Image 8) have been described in non-pregnant cows. Furthermore, ZEA is related to abortions, pseudopregnancy, decreased fetal viability, and general fertility disorder (Imagen 9) (Hartinger et al., 2022; Krska, 1999; Figueroa, 2007).

Milk production is also affected, with a drop in the quantity of liters produced and an alteration in its quality (Ogunade et al., 2018). Field observations suggest that high ZEA contamination in the final ration can trigger estrogenic problems, decreased feed intake and milk production, vaginitis, vaginal secretions, reproduction deficiencies, and increased mammary gland size in heifers (Gimeno and Martins, 2003).

Image 8. Enlargement of the vulva, uterine or rectal prolapse.

Image 9. Presence of ovarian cysts and abortions.

This mycotoxin can also trigger significant problems in males. Some authors have described cases of sterility caused by its oxidative effect (Liu et al., 2023), complemented by findings of testicular atrophy and feminization (Figueroa, 2007). Finally, zearalenone also causes systemic damage at the hepatic and renal level, as well as pulmonary edema (Hartinger et al., 2022).

Ergot alkaloids

Significant ergotism outbreaks were described in cattle and horses in the 90s, following the feeding of wheat and oats infected with Claviceps purpurea (Ilha et al., 2003; Riet-Correa et al., 1988, 2013). In the case of cattle, intoxication occurred due to the consumption of wheat bran, primarily presenting the distemperature syndrome.

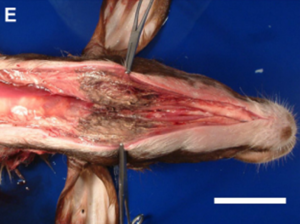

Intoxication by Claviceps alkaloids manifests in livestock in four main clinical forms: skin and gangrenous lesions of the tail and extremities (Image 10), hyperthermia with loss of production, reproductive failure, and a convulsive or nervous form (Burrows and Tyrl, 2001).

Gangrenous ergotism is the cutaneous form, associated with subacute or chronic ingestion of ergopeptide alkaloids. Loss of the ear tips and tail tip has been observed, and its mechanism is due to the constriction of small arteries and arterioles leading to necrosis, affecting all four extremities (Image 11). Low ambient temperatures intensify these effects. In this form, defined lines appear separating normal tissue from non-viable tissue, a putrid meat odor may be perceived, and affected animals may continue walking until the digits drop (Nicholson, 2007).

Image 10. Gangrenous lesions on the tail and limbs.

Image 11. Necrosis due to dry gangrene, claudication, and lameness.

The heat stress syndrome is related to hyperthermia (Image 12), noticed in exposed steers, even at moderate ambient temperatures and humidity (Bourke, 2003). Other neurological and systemic signs described include lethargy and hyperexcitability, and tremors (Image 13 and Image 14) that initially affect the neck and head and subsequently generalize, as well as episcleral congestion (Image 12) (Riet-Correa et al., 2013).

Image 12. Stress due to hyperthermia and episcleral congestion.

Image 13. Ataxia and tremors.

Image 14. Meningeal congestion in cattle with hyperexcitability.

T-2 mycotoxins

The T-2 mycotoxin is distinguished as one of the most detrimental fungal toxins for ruminants. Its effects are primarily cytotoxic and immunotoxic, severely affecting fundamental processes of the organism. This mycotoxin induces significant alterations in protein synthesis, including RNA and DNA, compromising energy metabolism and reproductive function. At the neurological level, T-2 toxin can cause tremors or paralysis in the hind limbs, according to recent studies (Ogunade et al., 2018; Kemboi et al., 2020). Systemic lesions are common, and damage is often observed in the bone marrow, liver, heart, nervous system, and mucous membranes.

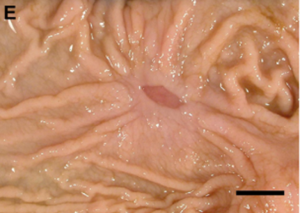

In addition to its systemic effects, T-2 exerts a direct impact on the sites of first contact, mainly the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and the skin (Image 15 e Image 16). These localized effects can persist even after toxin absorption. In the GIT, typical lesions include gastritis, abomasal and intestinal hemorrhages, and ulceration (Image 17). Damage to the organism’s blood vessels and damage to heart muscle cells (myocardial necrosis) (Image 18) also occurs. It is essential to note that in the preruminant stage (young animals), the effect is more acute and resembles that observed in monogastrics, given that the rumen has not reached its full detoxification capacity (Cope, 2018).

Image 15. Subcutaneous edema and necrosis in the neck and submandibular región.

Image 16. Necrotizing and purulent multifocal stomatitis (pharynx and tongue).

Image 17. Chronic multifocal ulcerative abomasitis.

Image 18. Multifocal cardiac pallor and myocardial fibrosis.

Deoxynivalenol

Ruminants that do not suffer from any metabolic alteration or inflammatory process are capable of inactivating significant amounts of deoxynivalenol (DON). However, the rumen microbiota can be affected in cases of altered fermentation, defaunation, or low ruminal pH (Whitlow and Hagler, 2007). In situations of high feed contamination, prolonged exposure, or compromised defenses, DON can reduce dry matter intake, compromise reproduction, and alter the immune system (Guerrero-Netro et al., 2021). Especially in calves, the ingestion of DON-contaminated feed leads to lower weight gain, lethargy (Image 19), and increase susceptibility to infectious diseases (Panisson et al., 2023; Hasuda et al., 2022; Ogunade et al., 2018; Nagl et al., 2014; Heliez et al., 2009; Pinton et al., 2009; Mallmann et al., 2007).

Image 19. Diarrhea, anorexia, and depression.

Fumonisins

The fumonisins family includes more than 30 different types, the most studied being those that act as sphingosine analogues. By substituting it in biological reactions, they cause failures in the cellular molecular structure (Fink-Gremmels, 2008). Primary damage is localized in the gastrointestinal tract, kidney, and liver (Hartinger et al., 2022). Although the toxin is poorly absorbed by ruminants and can be partially degraded in the rumen, systemic effects have been documented, especially with high exposure levels. In suckling calves, the kidney has been identified as the target organ for toxicity (Smith, 2018).

The most notable clinical symptom is the reduction in dry matter intake (DMI), which consequently leads to a decrease in milk production. Other associated effects include increased susceptibility to diseases (Fink-Gremmels, 2008), decreased ruminal fermentation, and microbiota alteration, effects that are more evident under stress or co-exposure with other mycotoxins (Gallo et al., 2020).

Ochratoxin A

Ochratoxin A (OTA) can cause kidney damage and failure (Image 20), oxidative stress, and liver damage (Image 21), as well as immunosuppression (Image 22). OTA has synergistic effects with ZEA, exacerbating the reproductive alterations induced by them.

Image 20. Friable, black, and autolytic kidneys.

Image 21. Hepatitis and perivesicular emphysema.

Image 22. Depression and weight loss.

Conclusion

The clinical symptoms of mycotoxins in ruminants are varied, depending directly on the nature, concentration, and duration of toxin exposure. These substances compromise animal health by causing immunosuppression, liver damage, metabolic alterations, and neurological or reproductive effects. Although the rumen offers limited detoxification capacity, high exposure demands an active response. Therefore, early detection of contaminated forages and the implementation of mitigation strategies are essential to preserve the defense system and minimize its impact, thereby guaranteeing animal welfare and livestock productivity.